Colorado Gold

The Grand Canyon is one of earth’s special places, and even in special places you come across spots that are extra incredible. The photo above is the confluence of the Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers in Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. During the majority of the year it looks like this. The turquoise colored waters of the Little Colorado, coming in from the right, are fed from a highly mineralized spring about six miles upstream. The Colorado’s waters come from Glen Canyon Dam, which filters out most of the sediment, leaving a deep green hue to the water, when the sunlight hits it. If there is a flood in the vicinity, either, or both, will turn muddy before returning to this two tone mix.

For this week’s challenge, I thought the changing of the Little Colorado’s waters after mixing with the larger volume of the main river showed the visual aspect of change. But there’s a far deeper issue of change at stake. The photo above is in National Park property, but about a mile east, just outside the right edge of the frame, is the boundary with the Navajo Indian Reservation.

A project called the Grand Canyon Escalade is still being considered to be built in the Navajo lands at the edge of the national park. The project’s main feature would be a gondola estimated to bring up to 10,000 people a day into the canyon. At the bottom would be restaurants, shops, an amphitheater and elevated riverwalk. You can also add toilets and garbage to that list. On the rim would be hotels and an RV center plus more of the previously mentioned items. They seem to have omitted where the water supply would be coming from.

The Escalade idea came from developer R. Lamar Whitmer, with the project offices based in Scottsdale, Arizona. Mr. Whitmer has several arguments for his cause, including making this area “accessible to those who might never get to enjoy the tranquil isolation at the bottom of the canyon”. Have you been to Mather Point on the South Rim, Mr. Whitmer? There can easily be a thousand people there at sunset, and the words “tranquil isolation” are the furthest thing from my mind. I can’t imagine experiencing tranquil isolation with thousands of strangers in this tight little pocket of the canyon. That is where raft trips fill the need quite well.

The major selling point of this project was jobs for the Navajo Nation, where unemployment is incredibly high. Nobody could possibly be against that, or could they? Written into the contract is a non-compete clause for 40,000 acres along access roads. It seems all those jewelry stands run by nearby families would have to go, among others. And how about that corporate address? I would have an easier time believing that the Navajos’ best interests were at stake if it was based in Window Rock, or Cameron, or even Flagstaff. Are the Navajo workers supposed to move or commute to Scottsdale? Or are the Navajos not even being considered for corporate level jobs?

This project is completely in the hands of the people of the Navajo Nation. There is nothing that US citizens or the US government can legally do to prevent this from becoming reality. The nearby Hopi tribe has no say in the matter, either. The spring which feeds the Little Colorado is one of the Hopis’ most sacred sites. Fortunately, newly elected Navajo President, Russell Begaye, is against the Grand Canyon Escalade. This is probably the best news to come about since this idea first started. His predecessor was completely for it.

In addition to the impact in the immediate area, this eyesore will be visible from many points along the South Rim, and those points on the eastern drive of the North Rim. The spot I was standing, even though considered backcountry, used to have a rough road leading all the way out to the overlook. Very few people knew of this, but it only took a couple of disrespectful people, having bonfires and leaving trash, to make it so you have to walk the last five miles now. I wonder what the impact will be when the numbers are in the thousands?

I really don’t want to add this to my historical photograph collection.

In response to The Daily Post’s weekly photo challenge: “Change.”

As an old friend used to say, “Every day above ground is a good day!” Some days stand out more than others, and here’s one that I still remember.

My friend Dave asked me to join him checking out a hike he had read about. It was the Taylor Creek hike in the Kolob Canyons section of Zion National Park in Utah. The National Park Service lists this as a 5 mile roundtrip hike that only gains 450 feet. Dave and I both have extensive hiking experience, including the Zion Narrows and many Grand Canyon hikes, so this sounded like something we would knock out in about 2 hours. The official trail ends at Double Arch Alcove, but he had read that going further up canyon was worth investigating. Even then, we both had the feeling we would be done early, and maybe that would leave time to hike another trail in the park.

We left Las Vegas about 8 am on a late April day. The forecast for Zion was sunny skies and about 80 degrees F. This placed us on the trail about 11 am, just in time for mid-day light. Neither one of us was expecting any great photographs, but it was a beautiful day, and any day hiking is a good day!

The trail started out in relatively open country and we could see higher canyon walls ahead. The easiness of the trail soon had us at an old cabin along the way. It didn’t seem like it was much longer when we arrived at Double Arch Alcove. This was an impressive sight and the depth of this beautiful canyon had become obvious. As we continued further up, there was a physically demanding spot or two, enough to keep the average tourist back. Then, our first unexpected sight came up. It was a large snowbank at the base of the canyon where water was trickling down. The cool air announced its presence before we had sight of it, and the snow was a bit on the mushy side, as one would expect in 80 degree air. We continued upward, and as we neared the end of our route we encountered another snowbank. This one, however, was completely different. It was several feet thick and rock hard. We referred to it as the desert glacier, and were estimating that it was still going to be there in June when the temps hit 100. It was shaded by steep walls of the final narrow box canyon. At the end of this box canyon were colors and textures that neither one of us had ever seen, and in a canyon so dark we needed a flash to capture it properly.

As we headed back, we couldn’t help but notice that there was a cloud or two floating above. The weathermen rarely get it right, and this day was no exception. By the time we got back to Double Arch Alcove, there was more cloud than open sky, and the light was becoming great for photography. Usually I’m the one who holds other hikers back under these circumstances, but Dave was fascinated with the changing light as much as I was. A hike which we should have finished in another 45 minutes took us almost 3 hours. Most of these photographs are along the official trail.

As we got back to the car, we knew we only had about a half hour before sunset, and we couldn’t leave just yet. We drove into the park about another mile and found a couple great spots to get more photos as the sun was going down. Afterwards, we headed down to St. George and filled up on a healthy dose of comfort food. What better way to finish out a very good day?

The challenge this week is half-and-half, and as I was looking through my photos I came across some lake shots. Those were mostly reflections, not two halves. Then I came across this one, half water (with some rock), half sky. This was sunrise from the island of O’ahu.

In response to The Daily Post’s weekly photo challenge: “Half and Half.”

My photography teacher said repeatedly, “If you see something that sparks your interest, take the photos now. It may not be there or look the same when you come back!” He lived in the desert in Carefree, Arizona, and I knew he was referring to Pinnacle Peak (above) on more than one occasion. At the time, developers were rearranging the map at an unprecedented pace on the perimeter of the metropolitan Phoenix area. The location of this photograph is either someone’s backyard or a golf course now.

It’s not just development that alters our world. Glacier covered lands don’t look the same as they did a decade ago. Weather can wreak havoc in a matter of minutes. Unforeseen disasters can happen at any moment. In today’s digital era, my teacher’s words don’t seem as relevant as they once were. You will never again hear someone say, “Hmmm, I don’t want to take that one. I’ve only got 8 shots left on this roll of film, and I don’t want to waste them.” Perhaps his message should be updated to “Keep an extra memory card in your bag at all times for those moments when you come across something special” 🙂

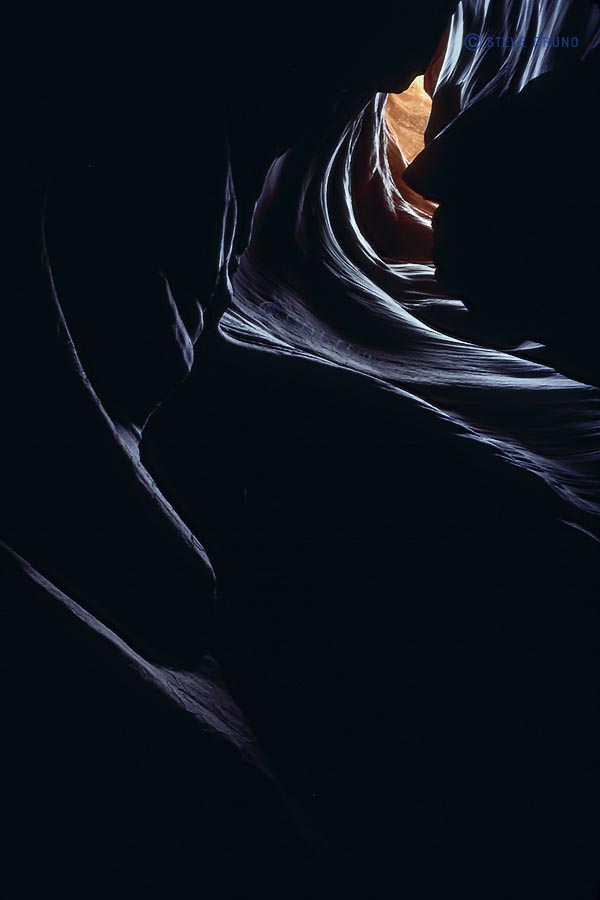

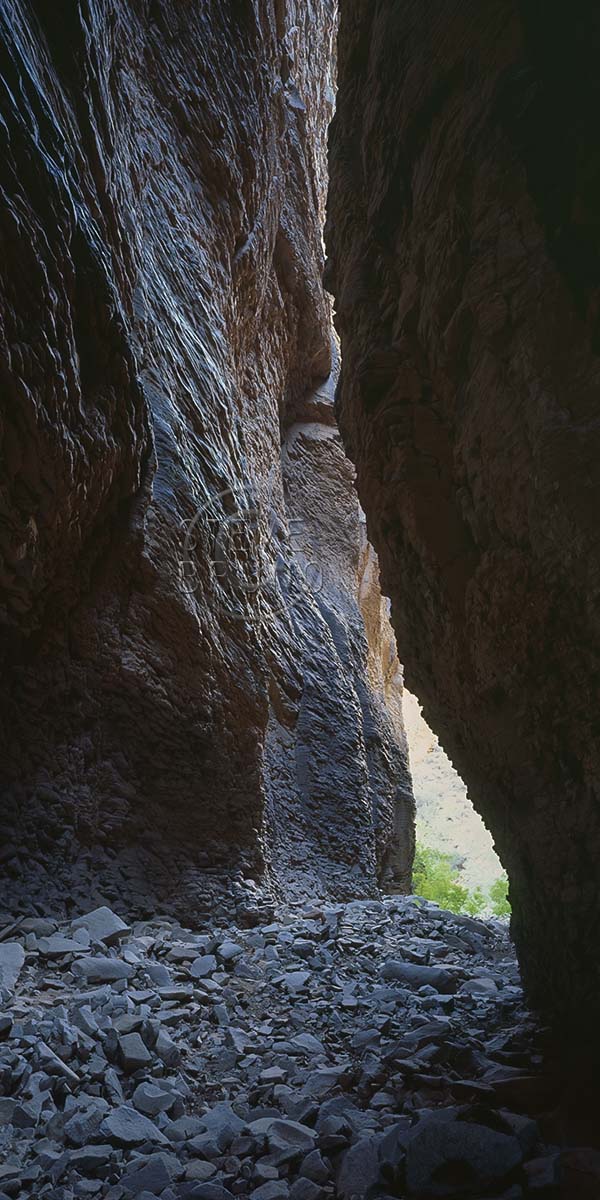

I’ve hiked many miles, and early on I discovered I preferred canyon hikes over those on a mountaintop or ridgeline. It’s not just about having shade or water, but more of the adventure of coming around a corner and being amazed with something unexpected. And while canyon exploring tops my list, some canyons are more memorable. Those are the ones where the skies disappear and I might have to take off the pack and step sideways for a moment or two. At that point, it’s hard not to feel enveloped in the land. Sometimes it’s challenging to find an angle to photograph these spots, because there’s no moving around for a better angle, and looking up just yields a washed out image. Whether it’s a slot canyon or just another thin slit in the earth’s crust, sunlight rarely penetrates to the bottom. If it does, the contrast is too much, so the best light is often reflected sunlight.

Here are some of my favorite places to become enveloped:

Top: small side canyon in Zion National Park, Utah

Second: Antelope Canyon, near Page, Arizona

Third: Cathedral Gorge State Park, Nevada

Fourth: unnamed canyon in Navajo Indian Reservation, Arizona

In response to The Daily Post’s weekly photo challenge: “Enveloped.”

First off, I would like to wish all the mothers out there a Happy Mother’s Day.

The photograph above was taken when I took my mother along with her mother on a several day excursion around northern Arizona and southern Utah. My mom has joined me a couple times since, but it was the only time for my grandmother. I kept the trip very ‘touristy’, and we all had an enjoyable time. Thank you, mom – for everything you’ve done for me and wanting to see my world.

Now, about the title. This photo was taken in July, 1983 when the waters of Lake Powell were at historically high levels. Winter snows had been abundant, and the temperatures stayed cool well into spring. Then, over a period of about a week, summer decided to move in. Although the authorities knew how much snowpack was in the upper Colorado River Basin, they hadn’t anticipated it melting this quickly. As they released water from the spillways of Glen Canyon Dam, they were losing ground to the inflow at the upper end of Lake Powell.

The spillways had never been worked extensively until 1983. They were run before for testing purposes, but never at full capacity. After a couple days, people noticed that the dam was vibrating. Engineers below the dam had observed chunks of concrete with rebar being ejected with water from the spillways. Water flows had to be cut back so as to not damage the spillways any further, and plywood sheets were attached to the top of the dam to potentially hold back the rising waters of Lake Powell. The Bureau of Reclamation contends that the dam was never in danger during this period. I’m not an expert, but I’m pretty sure a 710 foot high dam holding back trillions of gallons of water, which was now vibrating, was headed for disaster had they maintained the flows. After the floodwaters receded, repairs were performed on the spillways which ended up going full throttle again the following year.

Needless to say, there is still a Lake Powell. If the Sierra Club had their way, we wouldn’t. The organization fought the initial construction of the dam, and has even made recent campaigns for its removal. It was around 2000-2001 when I remember seeing billboards around Phoenix where the Sierra Club was asking to ‘restore’ Glen Canyon. This falls under the category of ‘be careful what you wish for’. In 2005, several years of drought had brought the lake levels down 150 feet. Parts of the canyon that hadn’t been seen in over 30 years were now accessible. Forecasts are still predicting long-term drought, and this is something we may see again. For now, if you want to see what it was like pre-Glen Canyon Dam, check out the book “The Place No One Knew” with the photographs of Eliot Porter.

A little closer to present day we have the photograph below, taken in 1996. I had no intentions of duplicating the above photo. In hindsight, I wish I had taken one from near the same spot. If I had turned the camera the other way, you wouldn’t see much water. A small trickle and some pools in the creek bottom, and that was it. This time I hiked in, on what is one of my favorite hikes in the southwest. That’s Rainbow Bridge spanning the horizon.

To this day, this remains the most spectacular sky I have ever seen in Las Vegas, and certainly a top five anywhere. Unlike most photos where we only get to see a snippet of what’s happening, this sky had a similar appearance as far as I could see.

When I’m on the road, it’s a given that I will get up early to try to get the best light for my subject. This was in my backyard, relatively speaking. I had watched the weather segment on the news the previous night, and the timing of an approaching front looked as though it might coincide with sunrise, so I set my alarm. I drove out to nearby Red Rock Canyon, and well before the sun hit the horizon, I knew it was going to be incredible. The clouds were consistent, and not very low, so the color just came through in waves as the sun started to hit the horizon. It is the only time I’ve had friends call me later in the day to see if I was out there capturing the sunrise. Apparently, it was like a red beacon coming into everybody’s home in Las Vegas.

In response to The Daily Post’s weekly photo challenge: “Early Bird.”

We were in Yosemite in springtime, when a cold front passed through. The next morning there were chunks of ice floating down the river that hadn’t been there the previous mornings. We traced it back to the source – Yosemite Falls. The spray from the falls had built up a layer of ice close to a foot thick during the night and was now melting. This probably happens on a regular basis there, but I have never seen photos of it.

In response to The Daily Post’s weekly photo challenge: Afloat

The source for all the ice:

Here in Las Vegas, there is nothing 100 years old. I think it’s an unwritten law that a building must be imploded when it reaches 40 years, with something new and shiny replacing it. I had this shot in my files from the desert west of Salt Lake City, Utah. There were no historical markers or anything to indicate its age or any significance. I’m guessing its time to be from early 1900’s. Maybe a reader with more knowledge on building methods of the past might weigh in with some better info. In response to Sunday Stills Photo Challenge

I had several photographs that I considered posting for the ‘ephemeral’ challenge, and this was one of the runner-ups. Besides, it has a story. I’ve spent many days at the Grand Canyon. Months, if you tallied them all up. This was the most spectacular morning I have ever seen there, and this image was my reward for waiting it out.

The Grand Canyon has inversions, about once every several years according to the National Park Service. On those occasions, the whole thing fills with fog and lasts a while and doesn’t offer much of a view into the canyon. This wasn’t one of those events, but in a single still frame it may appear that way.

This morning started like any other. I got up at dark o’clock, crawled out of the sleeping bag, put on appropriate clothing and started my truck (my home on wheels at times). My sleep had been interrupted several times through the night by thunderstorms. Just when I thought they couldn’t get any worse, they did. I was camped in familiar territory in the National Forest outside the park boundary because it is a quiet spot – from people, anyway.

Cape Royal is the last stop on the North Rim Drive. It is only a couple miles away from the North Rim Village as the crow flies, but twenty-something miles for those of us in a vehicle. As I walked out to the point the sky had become less black, and I could see that there was potentially going to be a window in the clouds for the sun to make a grand entrance. The air was still wet, but it wasn’t raining. It was more like the wind was sucking away raindrops from the storms that were a couple miles away to the west, right about where the village and my campsite were. Meteorologists have a term for this, they call it ‘training’. One strong thunderstorm rolls through and sets up a favorable environment for others to follow. I think this one had four engines, because the caboose was nowhere in sight.

This was still the film era. There were no weather seals on my 4×5 camera, and those errant raindrops weren’t going away. As sunrise was getting near, I could see that the opening in the clouds was still there, but if the sun came through it was probably going to be muted. The overall look was still very gray and hazy. The thing that struck me as odd was the lack of people. The parking lot has room for over a hundred vehicles and I’ve seen it full, especially at sunset. Cape Royal is a great spot anytime because of its sweeping view and options for photographs.

Commence act one. The skies in my proximity were ugly, but the sun streamed across the Painted Desert with no obstructions. I was cringing. Raindrops were still drifting in from the west, and as long as that was happening, I couldn’t get a shot. As the sun hit them, they produced a full distinct double rainbow in a purple sky. It was absolutely insane looking! The spectacle lasted for at least five minutes before the color started to shift, and the spectrum became less intense. After another five minutes, the sun slid into the lip of the cloud cover and act two of the show began. All the cliffs below me were wet and glowing from the early morning sun. The colors were more intense than I had ever seen there. Rainwater pockets on all the mesa tops glistened like topaz crystals were strewn about, and I still wasn’t getting any shots. Neither was anybody else, because there still was nobody else.

Act two wrapped up and I wasn’t sure there was going to be an act three. It was back to being ugly gray with no more potential windows visible. But the air had dried out. Now? Really? I was so frustrated at the timing of it all. I knew I had witnessed a special morning there but had nothing to show for it. I headed back to my vehicle for some breakfast. Intermission, as I like to call it. Nothing to do but wait out the morning, and the vantage point from Cape Royal was the perfect place to catch any indication of a change in the light. The smell of rain-soaked sage and pine filled the air, I still had the place to myself, and the peacefulness of it all was refreshing.

Breakfast was over, and the sun started to win its battle against the clouds, making it brighter and warmer. I grabbed my camera and headed back out to the point. Enter act three. All that moisture below needed to escape into the atmosphere, and that warm late-summer sun was hitting stride. Slowly, little patches of fog began to congregate below me. There didn’t appear to be any more threat of raindrops, so I had my camera on its tripod. Despite it being well past sunrise, the colors were getting better. I began capturing images as the collection of cloudlets was gaining strength. Finally, as one big mass, they begin to lift, and roll across the mesa immediately below me. I was using a panoramic roll film back and clicking as fast as that camera would allow. The entire process would have been a spectacular time-lapse film clip, but I was glad to be capturing images at last. Then, almost as quickly as it came together, it all broke back into fragments and was dissipating. I was packing my camera up as I heard an enthusiastic voice on the rocks above me. “Hey, come see this!” the first of the sleeping villagers beckoned to the others. I felt like yelling out, “Show’s over – you missed it!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.